How can you use light to set your sleep schedule?

Humans are diurnal animals, meaning we sleep at night and are active during the day. This daily cycle of sleep and wakefulness is known as the circadian rhythm. Besides your sleep cycle, the circadian rhythm controls lots of your body’s other functions, including hormone levels, digestion, body temperature, and even immune function. But how does your body know what time it is so it can maintain this cycle?

Your body’s clock is all in your head

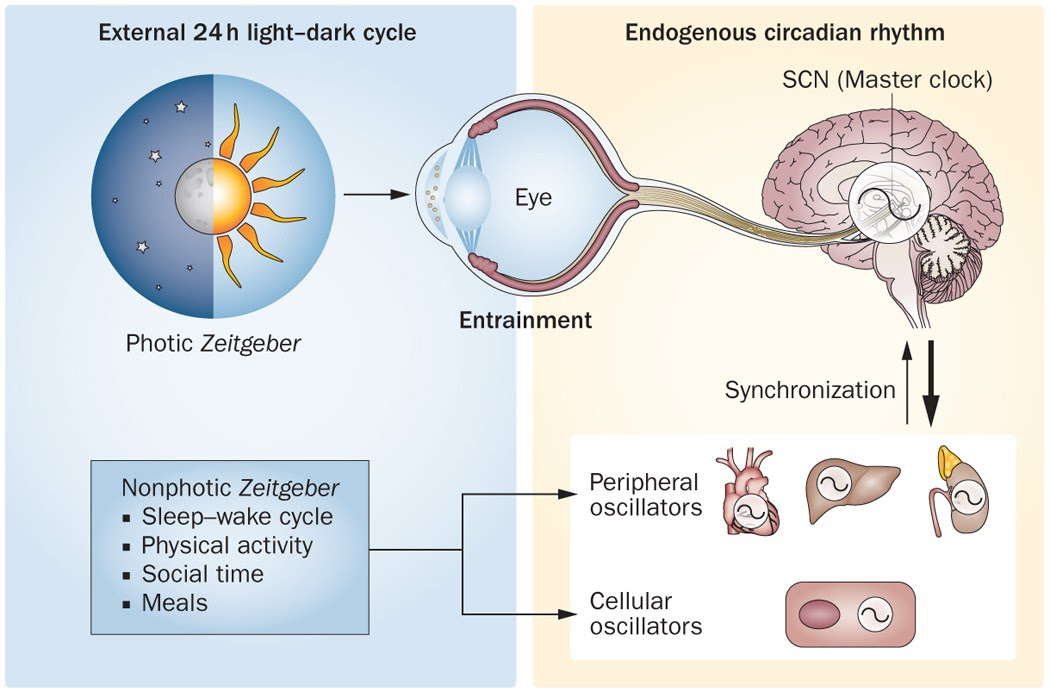

Most of the cells in your body have their own internal, molecular-scale clocks. A self-regulating network of genes and protein molecules turns sets of special genes (collectively called the clock genes, fittingly) on and off in a roughly 24-hour cycle.

This internal genetic clock is especially important in the neurons in your brain. A tiny region in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN, is the body’s master timekeeper. The circadian rhythm in the systems all over the body are kept in sync by the signals sent out from the SCN. The SCN neurons fire electrical signals throughout the brain and rest of the body more frequently and release more signaling hormones during the day, which is how the body’s main clock rhythm is transmitted to the rest of the body.

Image: suprachiasmatic nucleus. Source: Clocking in: chronobiology in rheumatoid arthritis

The SCN runs like clockwork

The body relies on the SCN to maintain its central clock, but how does the SCN itself know what time it is? How does it stay locked to the day/night cycle?

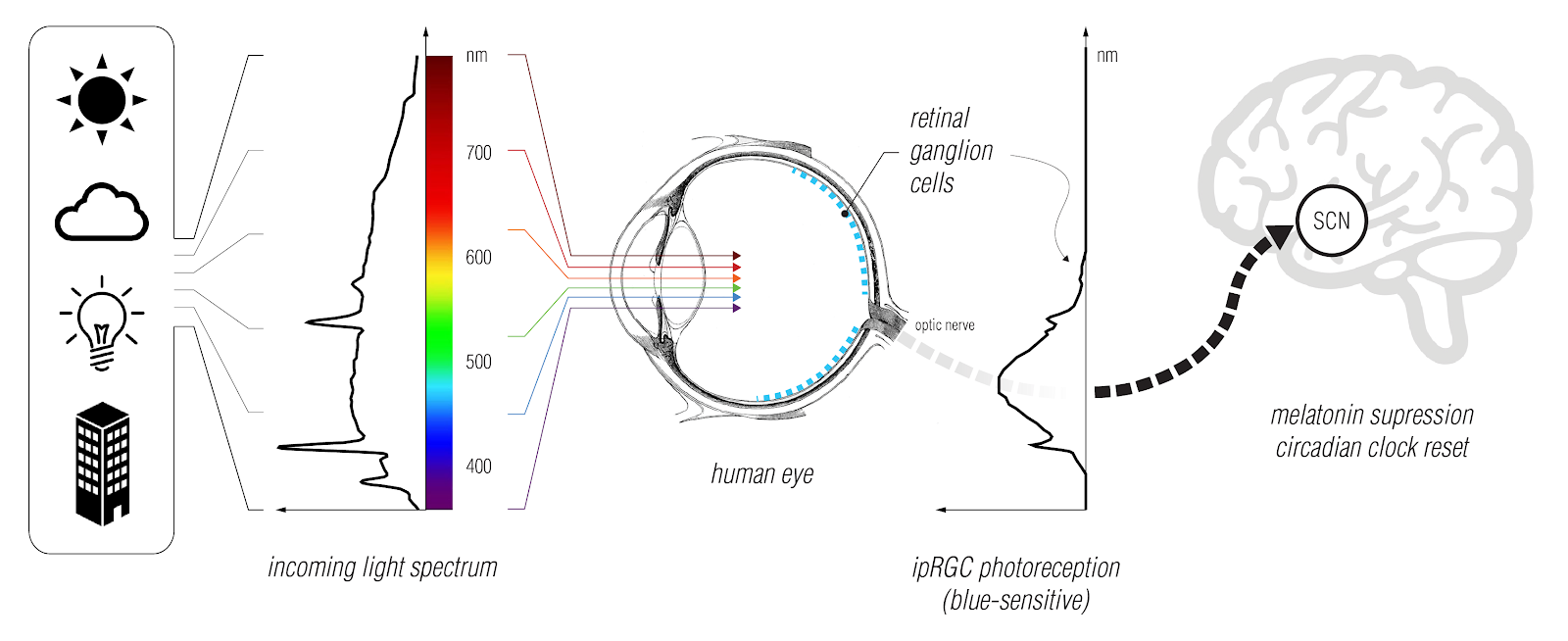

The main signal that adjusts SCN activity comes directly from your eyes. The layer of cells in the back of your eye that detects light, called the retina, sends electrical signals through a chain of neurons into your brain, which turns those signals into vision. Some of these neurons are connected directly into the SCN, allowing the central clock to very quickly receive environmental cues.

In an interesting twist, researchers have found that some of these SCN-signaling neurons in the eye can detect light themselves without first being signaled by the retina. In certain blind individuals, it was found that their circadian rhythm was still being regulated by these SCN-signaling neurons, even though visual information was not getting from the eye to the brain.

Light in the evening disrupts your sleep

As we have shared here before, the circadian rhythm has a huge impact on the length and quality of your sleep. Since light signals from your eyes directly affect your brain’s circadian rhythm control center, light exposure plays a central role in maintaining healthy sleep.

Studies have shown that exposure to bright light in the few hours before going to bed leads to greater alertness and shorter sleep times during the night. The SCN is in fact so sensitive to light during this time, the researchers found that even dim light interspersed with bright light was just as bad as continuous exposure to bright light.

Not only does light in general mess with your ability to get healthy sleep, but blue light in particular is known to cause issues with falling asleep. Commonly found emanating from phone and computer screens, blue light is especially effective at triggering the brain into activating its daytime patterns, suppressing nighttime hormones, and disrupting sleep.

Image: Impact of light on your SCN. Source: Sollema

Chronic nighttime light exposure has serious health effects

The world we live in may also force you to be exposed to light completely out of sync with your circadian cycle. Travel across time zones, resulting in jet-lag, forces your body’s central clock to be quickly out-of-step with the rest of your body’s rhythm. Hormone levels have been shown to be disrupted in jet-lag sufferers and may play a role in causing the physical effects of jet-lag. Long-term suffering from jet-lag because of frequent travel has even been associated with cognitive impairment.

Other long-term effects of nighttime light exposure can be seen in people working night shifts. Working at night causes the sleep schedule and circadian rhythm to be disjointed– adjusting sleep patterns to sleeping during the day and being fully awake at night results in fragmented sleep. This can result in signs of sleep deprivation, namely neurological symptoms like impaired learning and memory or mood disturbances.

Image: Melatonin levels in night shift workers show substantially shifted and reduced levels compared to daytime workers. Source: Papantoniou K, Pozo OJ, Espinosa A, et al.

Sleep patterns can even be disturbed by the seasonal changes in the timing of natural light exposure. Seasonal affective disorder, or SAD, is a form of depression associated with the decrease in daylight hours with the onset of fall and winter. Theories about its root cause implicate altered hormone release in the body and decoupling of the sleep-wake cycle with the body’s circadian clock. At this point, it is still unknown whether disrupted sleep is a cause of the neurological symptoms of SAD or if it is an effect of the out-of-sync circadian rhythms.

What can you do to help keep a healthy circadian rhythm?

Here are five tips for restoring a healthy sleep cycle in tune with your circadian rhythm.

- Decrease your nighttime light exposure: As studies have shown, exposure to bright light before bedtime disrupts healthy sleep patterns. Think about turning off your devices and turning down the lights to give your brain time to get out of day-mode in the hours before going to bed.

- Avoid blue light at night: Since blue light is especially effective at keeping your brain awake, invest in some blue light sleep glasses, enable night-mode, or download blue light-reducing software for your devices.

- Restore your body’s nighttime melatonin levels: The hormone melatonin is produced in your body during the night, and it is suppressed by exposure to light. Melatonin plays a key role in regulating sleep, and its levels and cycle is often impaired in individuals with chronic sleep conditions like SAD and jet-lag. Taking supplemental melatonin is one way to quickly adjust your body’s sleep cycle to different light patterns and circadian rhythm. We recommend these supplements from Thorne, the gold standard in science-backed supplements, to assist with readjustment.

- Start your day with some bright light: Bright light is associated with fast-acting increases in alertness, as well as suppressing the sleep hormone melatonin. The SCN is most sensitive to light during the evening and early morning in order to adjust the body’s circadian clock to daylight, so kickstart your morning with bright light to get your brain in gear.

- Track your sleep: Measure your sleep quality and duration with the Eight Sleep App to stay informed about your own sleep cycle and how you can keep a healthy routine. You can track your Sleep Fitness Score to see how changing your daily routine affects the quality of your sleep and get personalized sleep coaching to plan ways to get the most out of your sleep.

Dave Gennert is a contributing writer for Eight Sleep and a graduate student at Stanford University in the Department of Genetics. His research is focused on epigenetics in the immune system.